The fields and forests northwest of Verdun, bordered by the Meuse River on the east and the Forêt d’Argonne on the west, were the scene of the most intense fighting experienced by American forces during the First World War. The engagement raged from 26 September to 11 November 1918 and, because of the geography, became known as the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The combined French / American offensive was successful and contributed to the Germans seeking the Armistice which ended the war on 11 November.

Fighting northward through Varennes-en-Argonne, the Americans confronted a series of strong German defensive lines, or Stellung, given the names Hagen, Giselher, Kriemhilde, and Freya after characters in Wagnerian operas. The third of these was the most extensive and presented attackers with an almost continuous 10-mile belt of machine-gun positions and barbed wire. The terrain provided numerous opportunities for mutually supporting cross- and enfilade-fire and it exposed attackers to shelling from artillery hidden in the forests.

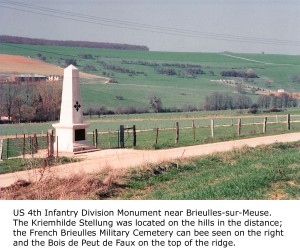

It was mid-spring 2005 and I had been in the area for several days reviewing the sites relating to the battle. On one particular afternoon, I drove the roadways near Brieulles-sur-Meuse to view the Kriemhilde Stellung terrain. Beside the road was a stone monument to the US 4th ‘Ivy’ Infantry Division, which had suffered 7,412 casualties in the brutal local fighting. I wanted a photograph and, contrary to my normal policy of finding a safe, public area to park, I instead turned onto muddy, farm track. After all, it was a quiet afternoon and nobody was about.

Struggling to get a perspective of the monument with the forests and hills of the stellung in the background, I climbed up a 7 foot verge and walked 300 feet or so along it. No sooner had I positioned myself, than I heard the rumble of heavy farm machinery. I knew immediately that it had to be coming down the farm track now blocked by my parked rental car. I hastened along the top of the verge and slipped down the steep incline in time to meet the tractor that had stopped just inches away from the car’s front bumper. I prepared myself for a tongue-lashing in French, or worse. The tractor’s driver stepped out of the cab and climbed down – presenting me with what I thought must be the largest farmer in northern France.

Struggling to get a perspective of the monument with the forests and hills of the stellung in the background, I climbed up a 7 foot verge and walked 300 feet or so along it. No sooner had I positioned myself, than I heard the rumble of heavy farm machinery. I knew immediately that it had to be coming down the farm track now blocked by my parked rental car. I hastened along the top of the verge and slipped down the steep incline in time to meet the tractor that had stopped just inches away from the car’s front bumper. I prepared myself for a tongue-lashing in French, or worse. The tractor’s driver stepped out of the cab and climbed down – presenting me with what I thought must be the largest farmer in northern France.

As he approached, I bravely stuck out my hand accompanied with the obligatory ‘bon jour’. He responded in kind. I mumbled the few French words that I knew including ‘premier guerre’, ‘monument’, and ‘Américain’. He smiled and responded with a few sentences that I barely understood. No matter. With an abrupt signal for me to follow him, he climbed back into his tractor and restarted its motor.

I followed him into the village to his farm where he again signaled for me to join him. He led me into a small room attached to the side of his barn. It was a narrow enclosure, perhaps eight feet wide and twenty feet long; probably originally meant to store tools and farm implements. However, now it was this French farmer’s private First World War museum. Benches covered in recovered artifacts bordered a narrow aisle; on the walls were hung weapons and wartime photographs. It was all neatly arranged; here a collection of rusted rifles with their wooden stocks completely rotted away; there groupings of colorful German wine bottles or belt buckles or shell casings. He had all the paraphernalia of the battlefield; bayonets, glass jars full of bullets, cooking pots, helmets, German beer mugs, brass knuckles, and more – anything that might be used in the deadly hand-to-hand trench warfare or in the mundane daily life of their inhabitants.

It seems that he owned woods and fields through which the Kriemhilde Stellung passed. Cutting lumber or plowing fields exposed these artifacts and he collected the remnants, cleaned off the mud, and started his own museum. As I wandered around the room, he proudly pointed out his most prized pieces. He spoke no English and I very little French, but no matter. We bonded over our common interest. His grandfathers stared out from two large photographs near the rear of the room; both served in the French Army and one was awarded six medals during the war at the cost of one leg.

After about one hour, I took my leave, but not until after I photographed the friendly French farmer standing proudly amidst his wartime collection.

© 2010 French Battlefields

PO Box 4808

Buffalo Grove, Il

USA

contact@frenchbattlefields.com

or Fax: 1-224-735-3478

web: French Battlefields

bonjour,

je suis le frère du “grand” paysan que vous avez rencontré à Brieulles et qui vous a montré son musée. Son prénom est Henri.

Nous nous intéressons tous les 2 à l’histoire de notre village, en autre, la guerre 1914/1918. Le monument de la 4ème Dius Ivy, signale l’avance extrême de cette unité en octobre 1918, elle a été relevée le 14 octobre par la 5ème Dius.

Merci pour la photo et le commentaire